I am a medical student at Penang Medical College under a twinning programme with the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland. I studied my pre-clinical years at RCSI Dublin. In the summer of 2015, I had the opportunity to join the RCSI Research Summer School (RSS) Programme. I was mentored by Dr Olga Piskareva, from Cancer Genetics, Molecular and Cellular Therapeutics (MCT) Department, RCSI. Being in this lab was simply one of the greatest experiences I have in my life; it was really rewarding.

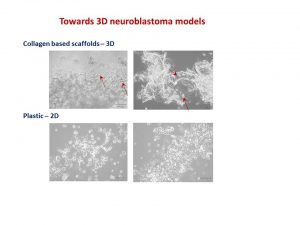

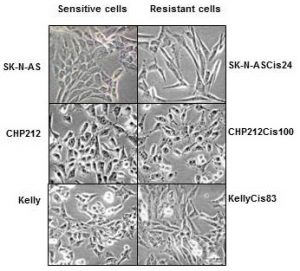

My RSS project investigated the role of VDAC-1 protein on chemotherapy resistance in neuroblastoma. The only research focus of this lab is to find key players in neuroblastoma pathogenesis and to advance anti-cancer therapy.

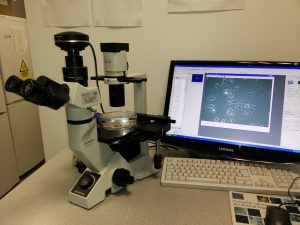

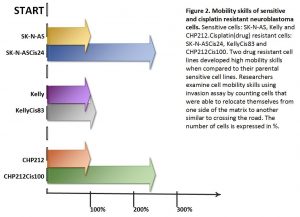

I was entrusted with the task of splitting cells. I would plate them onto 96-well plates, add cisplatin drug and measure their viability afterwards. It may sound simple here, but the whole process required passion and hard-work.

Prior to this, I did not have any experience in the medical research field. During my first two weeks, everything seemed so tough; however, they became easier as the weeks flew by. My mentor, Olga, and the other staff and PhD students (Garret, John and Ross) were helpful and always guided me to explore my potentials. This programme taught me various new things which I would not have acquired on a normal day-to-day basis in school.

The people at Cancer Genetics were warm and wonderful. The hospitality, love and guidance cannot be quantified and words cannot express my immense gratitude towards them. It has been fascinating and I cherish every moment I spent there. We bonded over our weekly breakfast and tea sessions so well, and I am indeed grateful for being a part of this big family. It is my sincere wish that this positive spirit of togetherness will be preserved and will grow stronger in the future. This is something special, and I think ours is the best lab at RCSI!

Under this RSS, all the participants attended skills workshops and weekly Discovery Series lectures. We were also given a Biography of Cancer by Siddhartha Mukherjee to read; evidently a good read. Here are the links to the RCSI Research Summer School Student Testimonial Videos.

I returned to Penang Medical College to further my studies in my clinical years. I took part in the PMC Research Day 2016 in which I was awarded the First Prize in Oral Presentation. I would like to dedicate this success to Olga and everyone who has been with me throughout my time at Cancer Genetics. Without all the guidance, I would not have made it this far.

I strongly urge students to take part in the research opportunities, because you gain invaluable experiences that you do not get elsewhere. May whatever we do at the lab today make a difference in another person’s life someday in the future.

Mei Rin Liew