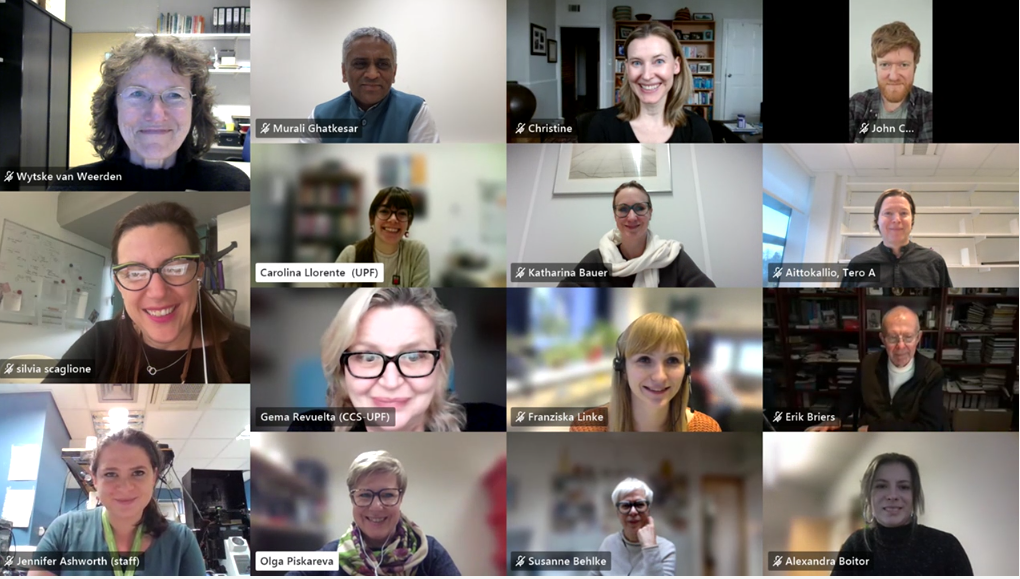

The European doctoral network Mac4Me (Macrophage Targets for Metastatic Treatment) has officially commenced its action with a successful kick-off meeting held in Rotterdam on June 25-26, 2025. The event, organised by the Erasmus University Medical Centre (the project coordinator), brought together the project’s core partners to harmonise efforts and set the stage for the next four years of research.

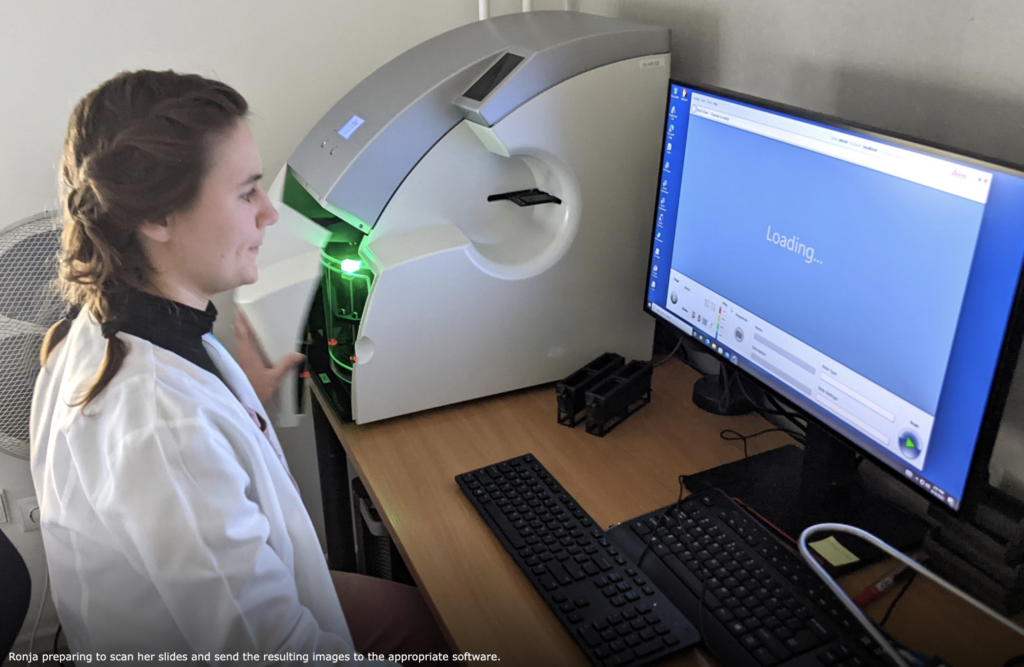

Mac4Me goes beyond technical expertise, striving to ensure each doctoral candidate has the tools to flourish both professionally and personally. This commitment was evident in the first training, which covered clinical aspects and requirements related to the three metastatic cancer types Mac4Me is focusing on. Besides advanced scientific methodologies, including single-cell mechanics and organ-on-chip technology, the students gained insights into fundamental biological mechanisms such as tumour formation, immune evasion, and DNA repair deficiency in age-related diseases. The training also explored the ethics of cancer research and included an activity in which the communication team produced short introductory videos featuring each doctoral candidate on the website. A significant part of the training focused on Patient and Public Involvement in Research (PPI). This session, led by patient advocates from Dublin and the US, fostered an immediate connection with the doctoral candidates, emphasising the importance of collaboration and direct patient engagement at every step in the research process. A profound mutual interest in the project’s success was shared.

With nearly all doctoral candidates and principal investigators meeting in person for the very first time, the training and the meeting were marked by a palpable spirit of eagerness and enjoyment. This initial gathering fostered strong team-building among the doctoral candidates and across the various subprojects, laying a crucial foundation for their scientific and technical collaboration. The meeting proved to be a success in promoting the exchange of expertise and significantly strengthening networking opportunities, thereby setting a precedent for ongoing collaboration.

Mac4Me is a Horizon Europe MSCA (Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions) Doctoral Network. The project is led by a core consortium of 14 partners and supported by an additional 11 associated partners. For more information about the consortium and the project, visit the Mac4Me website.

For media inquiries, please contact: mac4me@upf.edu.