In this row of journal club blog posts, I’ve decided to look at this study: A Tumor Microenvironment Model of Pancreatic Cancer to Elucidate Responses toward Immunotherapy.

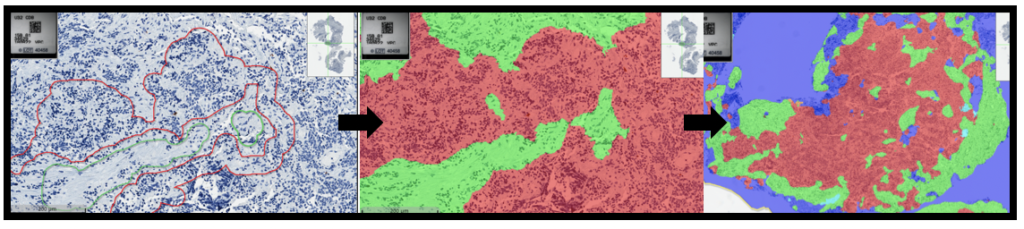

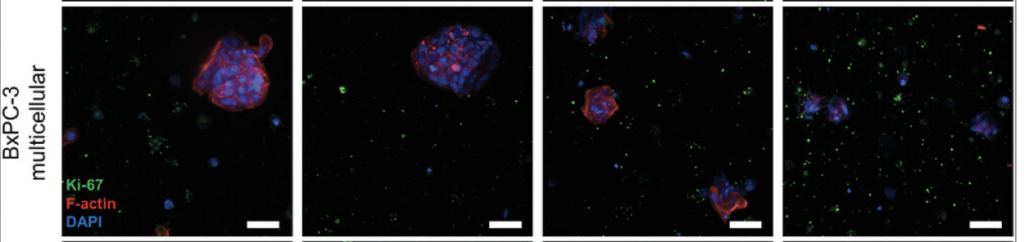

In this study, researchers developed an advanced model to simulate the environment surrounding pancreatic cancer cells. Using a specialized hydrogel matrix, they encapsulated pancreatic cancer cells, patient-derived stromal cells (non-cancerous cells that influence tumour behaviour), and immune cells. Within this matrix, the cells grew and formed spheroids, closely resembling the structure of tumours in the body. By fine-tuning the hydrogel’s properties, they controlled the stiffness and adhesion, optimizing conditions for cell growth and interaction, thereby enhancing the model’s resemblance to real-life pancreatic cancer. The researchers tested this model to evaluate its effectiveness in assessing new treatments, particularly immunotherapies. They treated the 3D cultures with a combination of immune and chemotherapy drugs and monitored the cells’ responses (See Figure). Notably, they focused on the novel drug ADH-503. Their findings revealed that the model accurately mirrored the responses observed in actual pancreatic cancer patients, confirming its validity for preclinical drug testing.

Furthermore, they explored the impact of these treatments on the secretion of cytokines—proteins crucial for immune regulation and tumour progression. They observed changes in the levels of specific cytokines (IL6 and IL8), indicating that the treatments could alter the tumour microenvironment and potentially improve therapeutic outcomes.

Overall, this study highlights the utility of their model for testing new therapies and gaining insights into the complex interactions within pancreatic tumours. It provides a robust platform for further research to develop more effective treatments for pancreatic cancer. While the study primarily focuses on pancreatic cancer, its findings and methodology have significant relevance to neuroblastoma research. Like pancreatic cancer, neuroblastoma is a solid tumour with a complex microenvironment that influences its growth and response to therapy. Thus, the model developed in this study, which accurately mimics the tumour microenvironment and allows for the testing of immunotherapies and combination treatments, could be adapted for neuroblastoma research. More directly relevant is the combination therapy of ADH-503 with immunotherapy and chemotherapy, underscoring the potential for this approach in treating other types of solid tumours like neuroblastoma. For my project, specifically, this study is helpful because it shows the relevance of immunotherapeutics on the immune cells present and their behaviour, which I plan to investigate for neuroblastoma in the future.

Written by Ronja Struck