Today, we are celebrating International Childhood Cancer Day to raise awareness and to express support for children and adolescents with cancer, survivors and their families.

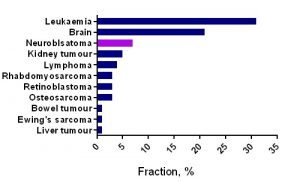

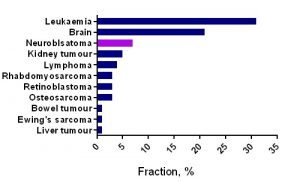

Childhood cancer is an umbrella term for a great variety of malignancies which vary by site of disease origin, tissue type, race, sex, and age.

The cause of childhood cancers is believed to be due to faulty genes in embryonic cells that happen before birth and develop later. In contrast to many adult’s cancers, there is no evidence that links lifestyle or environmental risk factors to the development of childhood cancer.

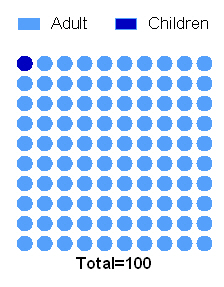

Every 100th patient diagnosed with cancer is a child.

In the last 40 years the survival of children with most types of cancer has radically improved owing to the advances in diagnosis, treatment, and supportive care. Now, more than 80% of children with cancer in the same age gap survive at least 5 years when compared to 50% of children with cancer survived in 1970s-80s.

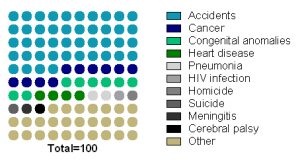

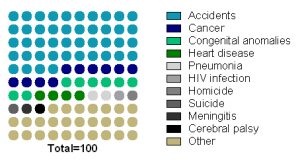

Childhood cancer is the second most common cause of death among children between the ages of 1 and 14 years after accidents.

Unfortunately, no progress has been made in survival of children with tumours that have the worst prognosis (brain tumours, neuroblastoma and sarcomas, cancers developing in certain age groups and/or located within certain sites in the body), along with acute myeloid leukaemia (blood cancer). Children with a rare brain cancer – diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma survive less than 1 year from diagnosis. Children with soft tissue tumours have 5-year survival rates ranging from 64% (rhabdomyosarcoma) to 72% (Ewing sarcoma).

For majority of children who do survive cancer, the battle is never over. Over 60% of long‐term childhood cancer survivors have a chronic illness as a consequence of the treatment; over 25% have a severe or life‐ threatening illness.

References:

Gatta G, Botta L, Rossi S, Aareleid T, Bielska-Lasota M, Clavel J, et al. Childhood cancer survival in Europe 1999-2007: Results of EUROCARE-5-a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2014.

Howlader N, Noone A, Krapcho M, Garshell J, Miller D, Altekruse S, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2011. National Cancer Institute.

Lackner H, Benesch M, Schagerl S, Kerbl R, Schwinger W, Urban C. Prospective evaluation of late effects after childhood cancer therapy with a follow-up over 9 years. Eur J Pediatr. 2000.

Ries L a. G, Smith M a., Gurney JG, Linet M, Tamra T, Young JL, et al. Cancer incidence and survival among children and adolescents: United States SEER Program 1975-1995. NIH Pub No 99-4649. 1999;179 pp

Ward E, Desantis C, Robbins A, Kohler B, Jemal A. Childhood and Adolescent Cancer Statistics , 2014. CA: Cancer J Clin. 2014.

This meeting is the biggest event for Irish cancer researchers.

This meeting is the biggest event for Irish cancer researchers.