This article by Krieger et al. discusses the most common form of brain cancer called glioblastoma. Due to its highly aggressive nature, research must be conducted consistently and rapidly to develop new treatments. This has proven challenging due to primary tumours being resected before further research can be done, as well as the lack of current technologies to fully explore relationships between GBM and surrounding brain tissues. This study aimed to study the aforementioned interactions in under 4 weeks, accounting for the rapid progression of the disease in real life.

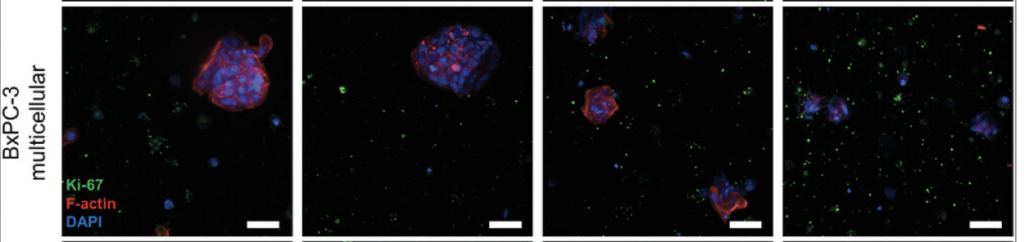

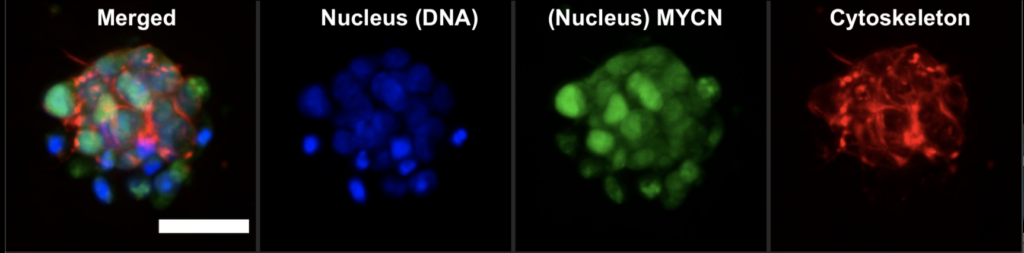

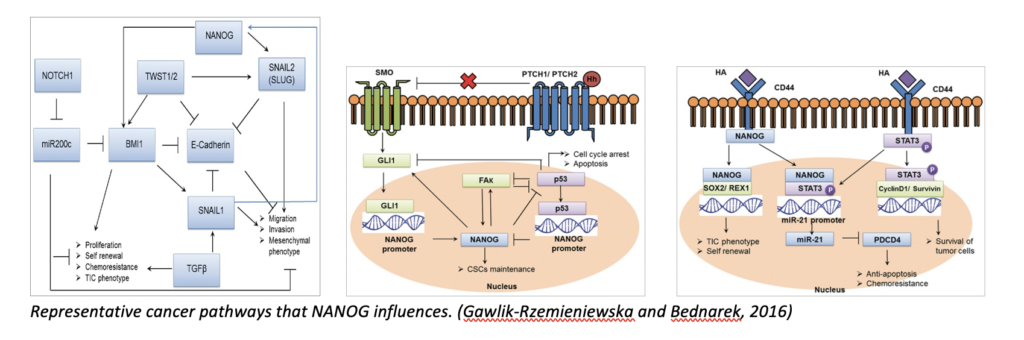

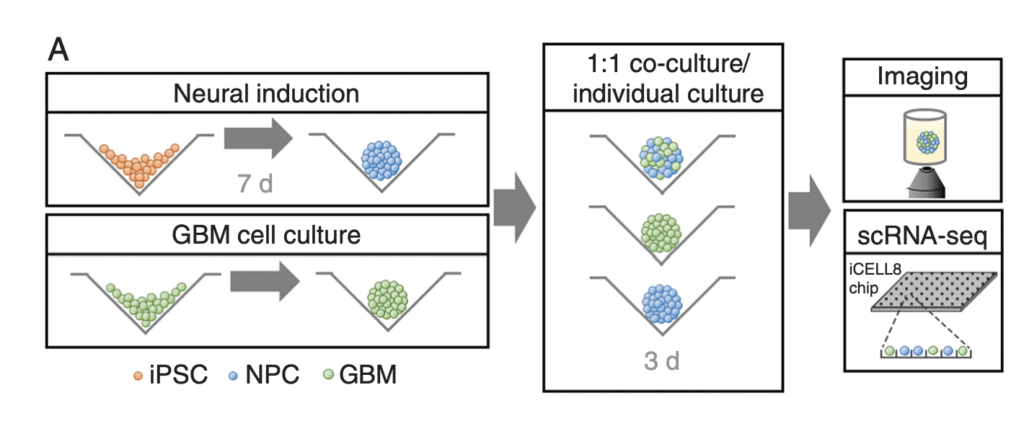

GBM cells were first derived from four patients and treated with glutamine, heparin, epidermal and fibroblast growth factors, then underwent a sequence of manipulations, such as second-generation replication lentivirus infection of GBM cells, iPSC line 409b2 inoculation in Aggrewell plates and later manipulation with invasion assays, and scRNA sequencing, which, along with the Aggrewell cells, produced neural progenitor cell spheroids for analysis. Confocal microscopy and the developed image processing algorithm allowed for visualization of these cells following fluoroscopy and depicted consistent growth of tumour cells. There was also the growth of microtubules. Any dissociated organoids were then co-cultured with GBM cells again, promoting interaction between the two. Further analysis revealed the upregulation of 45 genes, including PAX6, GJA1, GPC3, and others involved in cell regulation.

In conclusion, this novel mechanism of analysis of GBM cells using Aggrewell plates provided fruitful results, indicating intricate relationships between GBM cells and organoids, providing crucial insight for treatments by elucidating specific gene expression, heterogeneity of cells, and offering new targets based on ligand-receptor interactions. The particular relevance of this study to my work is regarding the usage of Aggrewell plates, which I am currently studying to determine how best to keep cells growing successfully within the wells. This article proves the usability and efficiency of Aggrewell and establishes its crucial role in the realm of brain cancer treatment research.

Written by Shreya Sankar