Walking in Mainz last week I saw a lovely fountain capturing 3 girls under umbrellas (Drei-Mädchen-Brunnen) at the ball square. This fountain was built between two Catholic girl’s schools symbolising the separate education and happy childhood. It has charmed me and reminded rainy days in Ireland and how this fountain may fit any park or square in Dublin.

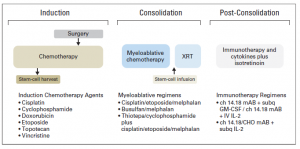

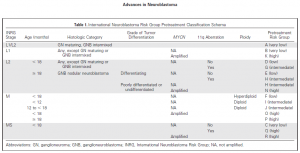

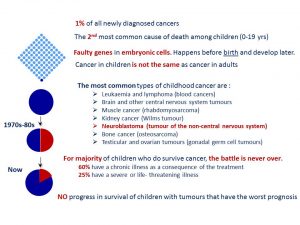

My second look at the picture gave me another perspective. This sculpture could illustrate not only happy childhood but also the protection we can give to children with cancer being their umbrellas. As September is childhood cancer awareness month, I am picking this picture to support this call. Raising awareness about childhood cancer we help to make their dreams come true. Dreams for better treatment, better quality of life full of love ahead through better funding of childhood cancer research and access to innovative treatments.

Today is the final day of

Today is the final day of  I was giving a talk at

I was giving a talk at