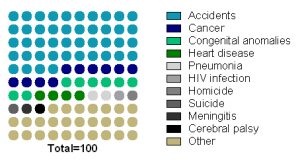

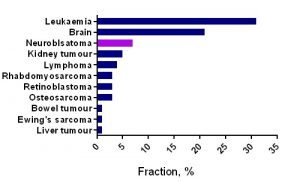

On April, 30th 2020, the 20K virtual race organized by Breakthrough Cancer Research came to an end. 1247 people participated and 496 completed this challenge. Together, we raised online over €50,000 to support their life-saving cancer research programmes.

As a scientist myself, I know that behind many current default living settings is intensive research in the past. IT would have never advanced if at some stage no discoveries in physics, chemistry have happened. We would have never been able to fight bacteria infection of no antibiotic was discovered. What about discovering of insulin? This list can go on and on… Just imagine if no research happens now. How we could cope with the current coronavirus pandemic? How we could help many people with cancer to have a healthier and longer life?

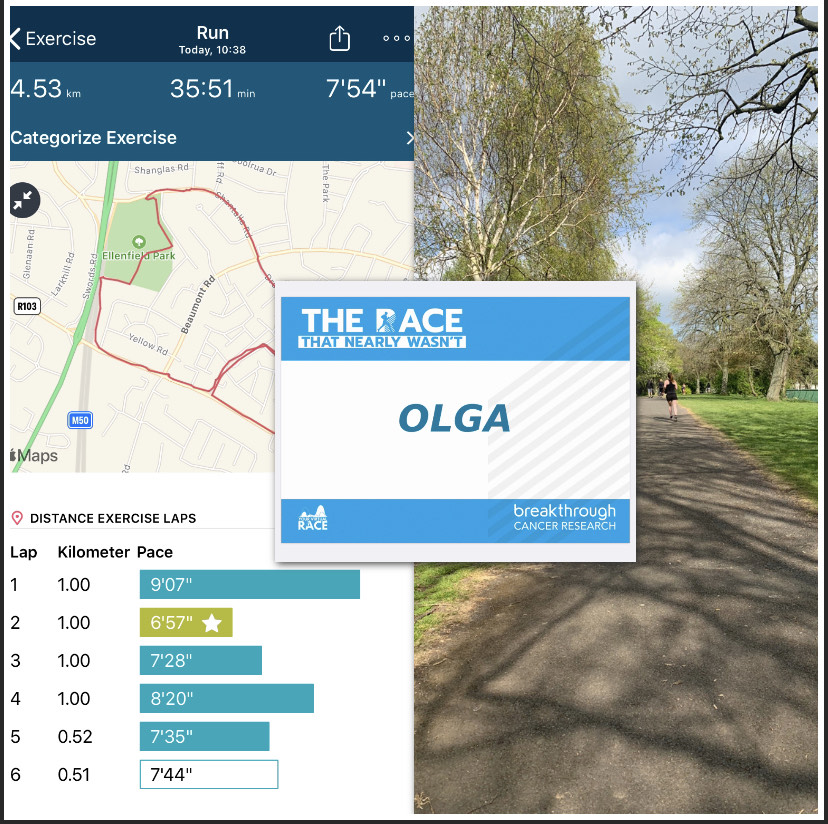

Breakthrough Cancer Research united many sports professionals and enthusiasts to build up a spirited community to support vital cancer research during the COVID-19 restrictions. I heard about this race by chance – my PhD student signed up to do it. When I read it, I thought it sounds achievable to complete 20K within a month. One small step at a time. It was a slow process. But it has transformed me.

At the finish line, I became addicted to my steady jogging within the allowed 2K distance every day. I have to confess that it is incredibly challenging for me to wake up, tie my sport shoelaces and go for a jog. My body wants a smooth transition from sleep to the active state, particularly when you are at home every day! This was normality in the past.

What did I discover going through this transformation? My body knows better its needs. Every morning I start it slowly with just an intensive walk. In 2-3 minutes, my body requests more fresh air in my lungs and higher endorphin levels in my blood. I can’t resist and start jogging. 🙂

Why mornings one may ask? I have tried different times during the day. My body has decided on morning hours even it is challenging… No option to negotiate.

Break Through Cancer Research are launching 40K and 60K May race. Could it be your chance for a transformation? Sign up today at: https://yourvirtualrace.com/theracethatnearlywasnt/