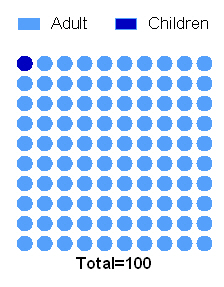

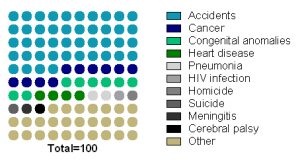

Children with neuroblastoma undergo several cycles of intensive chemotherapy to stop disease progression with the final aim to eliminate the tumour. Chemotherapy includes carboplatin or cisplatin in various combinations with drugs such as cyclophosphamide, ifosfamide, doxorubicin, etoposide, topotecan and vincristine (1). Nevertheless, in average 1 in 5 children with stage 4 disease do not respond to therapy. Up to 50% of children that do respond experience disease recurrence with tumour resistant to multiple drugs and more aggressive behaviour that all too frequently results in death.

The development of drug resistance is the major obstacle in treatment of neuroblastoma. To tackle this problem, researchers need to study different models of disease using cell lines, 3D tumour cell models, mice models and have access to clinical samples.

The first stage in testing drugs is to understand their killing ability of cancer cells. At this stage, researchers test drugs using cell lines. Cell lines are derived from tumours which were surgically removed from children with neuroblastoma. Researchers usually take a small piece of tumour straight after surgery and bring it into the laboratory. Here, they place this piece into special solution that has enzymes to separate cells from each other. Then the suspension of all kind of tumour cells is placed into plastic dishes or flasks in a highly nutrient media to let cells grow. Cells that can adapt to these conditions start to grow, divide and produce a new generation of cancer cells. Researchers look after their growth, inspect their shape and behaviour; and test them on the presence of tumour markers. Once identity of these cells is confirmed they become a cell line and obtain a name. These cells keep majority of characteristics of the parental tumour and represent very useful tools in cancer research.

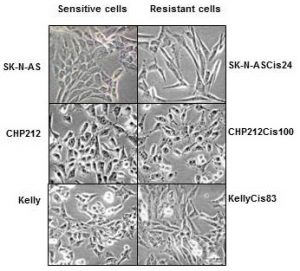

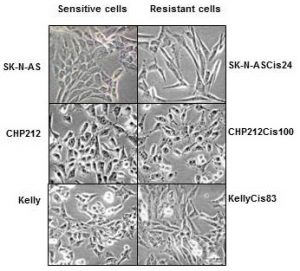

In our lab we use such cell lines to study neuroblastoma resistance to drugs. To understand changes in neuroblastoma biology during the development of drug resistance, we created drug resistant neuroblastoma cell lines (2). We treated three neuroblastoma cell lines CHP212, SK-N-AS and Kelly with cisplatin – a common drug in anticancer therapy. SK-N-AS and Kelly cells are sensitive to this drug, while CHP212 cells responded to this drug at much higher levels that the other two. Cells were grown in media containing cisplatin for several weeks. During this period most of the cells responded to cisplatin and died. Then we let cell survivors to recover in media without drug. This cycle was repeated several times until we got a population of cell survivors that can stand doses of cisplatin that can kill 50% of parental cells. It took us more than 6 months to generate cisplatin resistant neuroblastoma cell lines CHP212Cis100, SK-N-ASCis24 and KellyCis83.

At the next step, we studied differences between these cell lines. We first compared their behaviour and cell shapes. Two resistant cell lines KellyCis83 and CHP212Cis100 started to grow faster, but SK-N-ASCis24 – slower than their parental cell lines. Interestingly, these cells also became more resistant to other drugs such as doxorubicin, etoposide, temozolomide, irinotecan and carmustin. These results are very important as they demonstrate that one drug can activate the cell defense systems that allow to escape toxicity of other drugs. These cell lines can be used to test new drugs and find those that can overcome developed resistance.

Cisplatin resistant cells also changed their appearance. Most dramatic changes occurred in SK-N-ASCis24 cells (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Microscopic images sensitive and drug resistant neuroblastoma cells (adapted from (2))

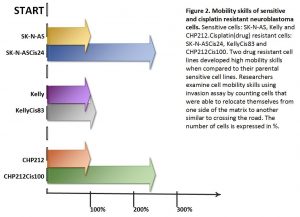

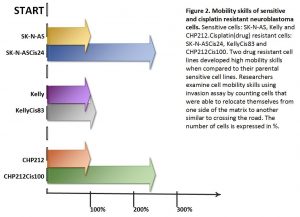

Two drug resistant cell lines SK-N-ASCis24 and CHP212Cis100 cells developed additional mobility skills – they became more invasive than their parental counterparts.

Then we asked a question: what type of changes allowed cells to adapt to cytotoxic environment? We examined changes in their genomic DNA first. We found that some genes increased their copy number, other went missing.

We identified changes in protein expression. More intriguingly, some proteins with the increased presence in the cells did not increase their presence in genomic DNA. We sorted these proteins on their role in cell processes such as migration, growth, cell cycle, etc. We found that each cisplatin resistant cell line developed a unique set of features that help them to escape cytotoxic stress (2). The similar patterns are found in clinic. Each patient responds to treatment differently.

What did we learn from this study?

- One drug, in our study cisplatin, can activate the cell defense systems that allow to escape toxicity of other drugs.

- The development of drug resistance gives cells new advantages and changes their behaviour and appearance, e.g. mobility skills, different cell shape, response to drugs, etc.

- Each cisplatin resistant cell line developed a unique set of features that help them to escape cytotoxic stress.

- These cell lines can be used to test new drugs and find those that can overcome developed resistance.

References

- Davidoff AM. Neuroblastoma. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2012; 21(1):2–14.

- Piskareva O, Harvey H, Nolan J, Conlon R, Alcock L, Buckley P, et al. The development of cisplatin resistance in neuroblastoma is accompanied by epithelial to mesenchymal transition in vitro. Cancer Lett. 2015;364(2):142–55.