It seems I have got a conference season. Three conferences within 2 months – no complains though. This time I went to the Matrix Biology Ireland Meeting in Galway. It was fantastic mix of topics and speakers ranging from new approaches in bone and heart repair to new matrixes in reconstruction of body tissues and diseases in the lab to minimise use of animals in pre-clinical studies.

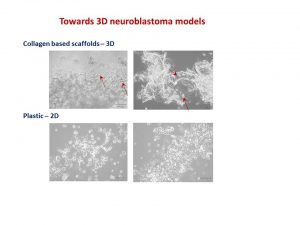

My talk was focused on neuroblastoma microenvironment and cell-to-cell communication through exosomes. I wrote about it in October post. I talked about things that did work and did not as well as new directions. One of the new directions is reconstructing neuroblastoma by growing neuroblastoma cells on collagen based scaffolds in 3D. Collagen constitutes most of our tissues to keep it shape and strength. These scaffolds are sponge-like matrixes built from collagen and other components. Of course cells grow differently on these matrixes. They have a different shape and growing properties in 3D. Neuroblatoma cells look like water drops on the cotton wool-like collagen scaffolds. In contrast, when they grow on plastic in 2D, they are flat. Studies show that cells in 3D respond to cytotoxic stress in a similar pattern as if being within a body (details in recent reviews 1-4). It would be a great breakthrough once these models are optimised for neuroblstoma research field. It will help to test all new and known drugs in the environment close to clinical settings. It could be a step forward to personilised therapies for children with neuroblastoma by isolating cancer cells, growing them in 3D and testing how they respond to all therapies available. It will facilitate more efficient design of treatment for relapsed or poorly responding tumours, sparing patients unnecessary rounds of chemotherapy and ultimately increasing survival.

I’ve always felt that a selection of abstracts for an oral presentation is biased. The overall background and views of conference organisers would affect works selected for an oral presentation. The same abstract was not selected for an oral presentation by one committee, but was supported by the other. Never give up!

Readings:

- Schweiger PJ, Jensen KB.Modeling human disease using organotypic cultures. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2016 43:22-29.

- Salamanna F, Contartese D, Maglio M, Fini M. A systematic review on in vitro 3D bone metastases models: A new horizon to recapitulate the native clinical scenario? Oncotarget. 2016 7(28):44803-44820.

- Picollet-D’hahan N, Dolega ME, Liguori L, Marquette C, Le Gac S, Gidrol X, Martin DK. A 3D Toolbox to Enhance Physiological Relevance of Human Tissue Models. Trends Biotechnol. 2016 34(9):757-69.

- Nyga A, Neves J, Stamati K, Loizidou M, Emberton M, Cheema U. The next level of 3D tumour models: immunocompetence. Drug Discov Today. 2016 21(9):1421-8.